REVIEW

A Review of Alison Powell's On the Desire to Levitate | Frank Montesonti

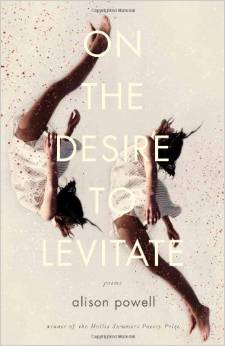

On the Desire to Levitate by Alison Powell

Ohio University Press, 2014 (64 pages)

ISBN: 978-0821420980

Ohio University Press, 2014 (64 pages)

ISBN: 978-0821420980

Gravity is the force that pulls us toward the earth, earth and all of its inescapable realities like family, culture, living, dying, landscape, and love. Alison Powell in her debut collection of poems On the Desire to Levitate, writes, "Who can stomach these parlors." The implied answer is that few of us can. Most of us need some hope of escape, some way to lighten the load even for a moment, to levitate.

Levitation is a symbol that depends on one of our most basic spatial metaphors: 'up' is good and 'down' is bad. Down is earth, the mundane, the changeable, the sordid, the body, desire, and death. 'Up' is heaven, the realm gods and angels. It is

purity, the unchanging, the essence, the untouchable. To levitate is to straddle these worlds, to be of both earth and sky. The tension in the poems in the collection come from the alternating pull from heaven and earth.

Of the two, the pull of their earth is the stronger force. The poems in the collection are grounded in earthy, Midwest landscapes among tractors, nests of copperheads, and tin roof barns. These scenes have a gravity that pulls us back to particular seasons in the speaker's life, like in the poem "Summer":

My grandfather in overalls the wild

blue of a storm sky. Me behind him

on a tractor, hands out, veering around plum

trees. Me by the beetle bag, squeezing,

The chemical smell out of them.

The images carry conflicts. The first line omits a comma to run together the image and juxtapose the quotidian farmer on a tractor against the supernatural danger in the sky. The sky is "wild" and everything wild is dangerous and alluring. The child rides arms out on the heavy tractor imagining she is a plane, the desire to defy gravity already emerging. The strange beetle bag releases something new, unexpected and foreign when touched, like a metaphor itself. The pull of the earth, the allure of the heavens, and the power of language as a transformative medium are themes that develop through the rest of the collection. The ending of "Summer" considers again the power of the worldly, the stronger force, how the things of this world leech into our very knowing:

[…] I would sit

on the stone floor before the fringed rocking

horse—its old gold eyes half-popped, broken.

Nose to metal nose, I learned the family secrets.

The child sits on an equal footing, rooted to the scene, and through those roots she absorbs knowledge beyond the things themselves.

In many poems the body and the environment begin to merge and the figurative rooting is taken further. In "The Fields" Powell begins: "A boy is raised up in the fields./ He knows his hard feet in the husks." The operative word is "knows." It is only through melding with the earth that he gains knowledge. The metaphor is hard to escape. The fields leech in. In "Eminence" the speaker of the poem describes losing her virginity in the cornfields.

Ground was soft, grave-ground; the whole of it swept

by a corn borer, tunneled in stalk. At harvest

we did it and the nights after — it crept

toward us, land felled acre by acre, […]

The threat here isn't the loss of any idealized innocence, but rather the larger, more menacing threat of knowledge binding us to the earth. Again the land figuratively threatens to consume. It "creeps" toward the speaker and her lover, threatening of harvest and of death. And in the end, it wins; the speaker melds with the earth.

[…] the next breakfast Mom said

"That crop's trying not to fail us — I heard it grow

last night," hands on her floured jean pockets

making me squirm. It was me she heard.

The mother mistakes the sound of the daughter for the squealing of corn growing, and the speaker in the poem squirms not only at her mother's possible knowledge of her secret act, but also at the eerie inability to separate herself from the fields. Once again, knowledge as entanglement with earth. Sometimes this is frightening. In the poem "Edema" the grandmother's ring melds to the bone of her finger and the only solution is amputation. The image is a warning. "This is your/ inheritance," says the mother to the daughter in the poem, "Florida". The daughter is confronted with the realities of age, place, and family. In the poem "Rodger's Road" Powell sums up the pull of the earth in single image, she writes, "At the farm across the way, horses tamped/the ground to emphasize their sureness of it."

Yet, there is something in the Midwest's earthy landscape that makes the head naturally turn heavenward, that makes us desire the up, the divine, the escape. The same boy in "The Fields" who "knows his hard feet in the husks" runs out in the rain yelling into the sky, "Oh! Great Harbor, I am/ your tin ship!" He imagines himself as something not connected to the earth— a ship, something floating. He is a "tin ship", something small and fragile. He begs of a harbor, a place of safety from the dangers of the earth. Ideas of floating, flying, or escape, counterbalance the pull of the earth. In the poem "Flyover Country" which begins, "we would fly over it if we could" a group of children play "Light as a feather, stiff as a board", a game that involves both the illusion of floating and the power of incantation. In the title poem, Powell writes, "[…] What strength/ in silence, to lift like that, over so many Nos. A calm braided/ embrace — There she goes." The earth is the place of rules, of "Nos", the lifting is the cathartic escape we feel in the italicized dreaminess of "There she goes." It's the pull of the earth that creates the desire to be free of its bonds. Her poems feel like that trick where you hold two heavy buckets out in each arm and when you drop them, your arms automatically rise.

Inverting the desire to rise, the book explores the notion of the fall. Hercules, Hylas, Eurydice, and Orpheus,—all Greek gods that share the trait of coming from heaven and getting stuck on earth, speak in persona poems. Hercules was half-man, half-god. Hylas was a god transformed into a copse of trees. Orpheus descends into the realm of gods but doesn't return with what he desires. Orpheus proclaims, "No matter where I go here in limbo/ the muteness of you extends, riotous." Limbo is a problem for the gods as it is for the humans. In "After Paradise Lost," Powell writes "[…] the earth is just beyond chaos, and so rests against chaos." No one likes chaos, not even the gods. No one wants to be stuck in limbo. And limbo is the conflict throughout the book.

If the pull toward earth and its chaos is the problem, the book suggests methods of resisting its pull. Powell writes, "The earth has something called an offering." Stressing that we have some way of communing with the heavens, of staying in touch. One of these offerings is song — the lyric impulse itself — for to sing is let go, a cathartic act, a break from silence. It is a magic act. Orpheus strikes the lyre and we are all transported. Powell, writes in the collection's title poem, "Shell game/ of sentences, release me from tenuous humans everywhere." In this statement she proposes language as a solution to the problem of human tenuousness. She writes, "I have been a cage; and cagey". If the earth is a cage, then one must by sly, deft to escape. Language and song are tools of this cageyness. The smart, lyrically tight poems in the collection become an offering, a means of escape, like the following poem.

Shargri-La.

Draw me a hangman's portrait. Draw me a fine girl

in the river. Draw me against the black of your eyes.

Draw me and what I give—lips drawn, still singing.

Draw Shargri-La, you did, did you, the year you left

with only the blues: lucky, but still. The fine girl

in the grass. We've been laid down, yes-yes, say yes,

a mouth rubbed all in tequila and sea salt, a famished

belly and you kissing it. And shadow of limestone,

and the barn, and mazes out of cornstalks. O

tanned—what legs! Inside your jeans.

Draw each thing that keeps you breathing, draw

your kitchen sink, draw a bath for coupling. My

I still love you, am drawn to your wicked ways,

to your sleepy ways, to your underwater, tiny,

sweet ways. Draw me a mouth, a red red mouth.

"Shangri-La" is pure lyric. The tone is ecstatic. The desire is only to sing. Each line is packed with reversals, leaps, sonic smartness, and lyric bravado. The operative word in this poem is "draw." To create. The idea of creation is amplified. The mouth, the instrument of singing, is not just red, but doubly red, doubly desirous. Singing breaks the bonds of gravity, the pull toward earth. On the Desire to Levitate lives up to the collection's title. In these smart, heartfelt poems, the reader can feel his or her heels lifted slightly from the ground, suspended in that realm between heaven and the earth were good poetry resides.

Of the two, the pull of their earth is the stronger force. The poems in the collection are grounded in earthy, Midwest landscapes among tractors, nests of copperheads, and tin roof barns. These scenes have a gravity that pulls us back to particular seasons in the speaker's life, like in the poem "Summer":

My grandfather in overalls the wild

blue of a storm sky. Me behind him

on a tractor, hands out, veering around plum

trees. Me by the beetle bag, squeezing,

The chemical smell out of them.

[…] I would sit

on the stone floor before the fringed rocking

horse—its old gold eyes half-popped, broken.

Nose to metal nose, I learned the family secrets.

In many poems the body and the environment begin to merge and the figurative rooting is taken further. In "The Fields" Powell begins: "A boy is raised up in the fields./ He knows his hard feet in the husks." The operative word is "knows." It is only through melding with the earth that he gains knowledge. The metaphor is hard to escape. The fields leech in. In "Eminence" the speaker of the poem describes losing her virginity in the cornfields.

Ground was soft, grave-ground; the whole of it swept

by a corn borer, tunneled in stalk. At harvest

we did it and the nights after — it crept

toward us, land felled acre by acre, […]

[…] the next breakfast Mom said

"That crop's trying not to fail us — I heard it grow

last night," hands on her floured jean pockets

making me squirm. It was me she heard.

Yet, there is something in the Midwest's earthy landscape that makes the head naturally turn heavenward, that makes us desire the up, the divine, the escape. The same boy in "The Fields" who "knows his hard feet in the husks" runs out in the rain yelling into the sky, "Oh! Great Harbor, I am/ your tin ship!" He imagines himself as something not connected to the earth— a ship, something floating. He is a "tin ship", something small and fragile. He begs of a harbor, a place of safety from the dangers of the earth. Ideas of floating, flying, or escape, counterbalance the pull of the earth. In the poem "Flyover Country" which begins, "we would fly over it if we could" a group of children play "Light as a feather, stiff as a board", a game that involves both the illusion of floating and the power of incantation. In the title poem, Powell writes, "[…] What strength/ in silence, to lift like that, over so many Nos. A calm braided/ embrace — There she goes." The earth is the place of rules, of "Nos", the lifting is the cathartic escape we feel in the italicized dreaminess of "There she goes." It's the pull of the earth that creates the desire to be free of its bonds. Her poems feel like that trick where you hold two heavy buckets out in each arm and when you drop them, your arms automatically rise.

Inverting the desire to rise, the book explores the notion of the fall. Hercules, Hylas, Eurydice, and Orpheus,—all Greek gods that share the trait of coming from heaven and getting stuck on earth, speak in persona poems. Hercules was half-man, half-god. Hylas was a god transformed into a copse of trees. Orpheus descends into the realm of gods but doesn't return with what he desires. Orpheus proclaims, "No matter where I go here in limbo/ the muteness of you extends, riotous." Limbo is a problem for the gods as it is for the humans. In "After Paradise Lost," Powell writes "[…] the earth is just beyond chaos, and so rests against chaos." No one likes chaos, not even the gods. No one wants to be stuck in limbo. And limbo is the conflict throughout the book.

If the pull toward earth and its chaos is the problem, the book suggests methods of resisting its pull. Powell writes, "The earth has something called an offering." Stressing that we have some way of communing with the heavens, of staying in touch. One of these offerings is song — the lyric impulse itself — for to sing is let go, a cathartic act, a break from silence. It is a magic act. Orpheus strikes the lyre and we are all transported. Powell, writes in the collection's title poem, "Shell game/ of sentences, release me from tenuous humans everywhere." In this statement she proposes language as a solution to the problem of human tenuousness. She writes, "I have been a cage; and cagey". If the earth is a cage, then one must by sly, deft to escape. Language and song are tools of this cageyness. The smart, lyrically tight poems in the collection become an offering, a means of escape, like the following poem.

Shargri-La.

Draw me a hangman's portrait. Draw me a fine girl

in the river. Draw me against the black of your eyes.

Draw me and what I give—lips drawn, still singing.

Draw Shargri-La, you did, did you, the year you left

with only the blues: lucky, but still. The fine girl

in the grass. We've been laid down, yes-yes, say yes,

a mouth rubbed all in tequila and sea salt, a famished

belly and you kissing it. And shadow of limestone,

and the barn, and mazes out of cornstalks. O

tanned—what legs! Inside your jeans.

Draw each thing that keeps you breathing, draw

your kitchen sink, draw a bath for coupling. My

I still love you, am drawn to your wicked ways,

to your sleepy ways, to your underwater, tiny,

sweet ways. Draw me a mouth, a red red mouth.

Frank Montesonti is the author of two full-length collections of poetry, Blight, Blight, Blight, Ray of Hope,

Winner of the 2011 Barrow Street Book Prize chosen by D.A. Powell, and the book of erasure, Hope Tree (How To Prune Fruit Trees)

by Black Lawrence Press. He is also author of the chapbook, A Civic Pageant, also from Black Lawrence Press.

His poems have appeared in journals such as Tin House, AQR, Black Warrior Review, Poet Lore, and Poems and Plays, among many others.

A long time resident of Indiana, he now lives in Los Angeles and teaches at National University.