REVIEW

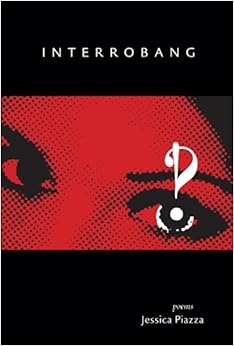

Fear, Love, and Iambs: A Review of Jessica Piazza's Interrobang

Red Hen Press, 2013 (72 pages)

ISBN: 978-1597097222

It's difficult in poetry to perform vulnerability. If intention precedes the line, I'll argue that the poem will have

already failed. When it's working, a maker will always be half a thought behind the phrase, and just a beat shy

of apprehending the next cluster of noises to forge meaning out of stirred air. Skill lies not in mastery or

control, but sensing when to give in, when to let go.

Which is why contemporary formal poetry continues to stun me. I mean, when it's good. I'll refrain from

enumerating criteria, which too often incriminates (critic and audience alike) and forecloses (pleasure and

possibility). For now, let's just agree that 'good' is both an intellectual and somatic experience, and what's

good attends, rather than appeals, to one's mind and heart. It is vigil or service, and not persuasion. Wit and

ingenuity being their own pleasures, a poem bound by meter and rhyme can be impressive enough, but to

successfully alloy those elements with feeling—as opposed to feelings' dross, sentiment—is true alchemy. A

feat.

But perhaps to pit 'appeal' against 'attend' is disingenuous, and neglects poetry's discursive history. I'll stand by my claim that what is good, before it is persuasive, is first attendant to the human condition. But allow me to amend: Love is the trickiest argument. A sonnet, its best rhetoric. And Jessica Piazza—the form's ablest practitioner. In her first collection, Interrobang, winner of the 2012 A Room of Her Own Foundation To the Lighthouse Prize, Piazza assembles our heart's complicated premises as clinical phobias and philias. Taking those vessels that science has fashioned for our worst fears and infatuations, Piazza pours out, and pores over, their impossible contents. What is most remarkable about these poems is how vulnerability reveals itself through, and not in-spite of, the form.

The book opens with an apologia of sorts. "Melophobia (A Fear of Music)" is an astute first poem, and speaks to what is scored and orchestrated in the following pages. Like a love affair, the crises and intricacies of which this book is replete, it begins with certain trepidation. At its center, the anxiety of the speaker is enacted by the stutter of "in" rhymes, clipped iambs, and the placement of 'now' which makes the line feel both harried and hesitant:

"to fail. A voice too frail, too thin, begin

again, again, again, now overwrought,

now under-sung; not done. They recommend"

"But we know possible is slippery."

Interrobang has not one, but three sonnet crowns, all of which navigate through distinct relationships, alternately stripping away and building up to its various revelations. It is no small pleasure to let the poems' technical virtuosities deepen their emotional resonance—one is first moved, then soon after, impressed. For those unfamiliar with a sonnet crown, its constraints can render most lines stilted. Piazza, however, inflects enough of these lines with idiomatic or conversational details that the iambs always feel authentically spoken; a verisimilitude of speech. They read like how any one of your friends might talk to you. Only better. Much, much better.

It is also testament to Piazza's technical acuity and narrative intuition that these discrete poems, and specifically these three sonnet crowns, arc into Love's phases, tracking how one's sense of self and the world can be shaped by human relationships. I'll venture one reading and say that the first sonnet crown ("People Like Us") is the relationship to a beloved or object of desire, the second ("The Prolific"), to one's environment or 'home', and the third ("What I Hold") to the self. Beyond the cyclical structure of the sonnet crown, I want to point to one moment in which echo and refrain work in and beyond each of these sequences.

In "The Prolific":

"He couldn't love me—I was not complete

the way his wishful eye completed me,

subtracting toward an ideal sum. I'd see

myself lost part by part: white neck, large feet,

wild hair—erased—a disappearing hand

pressed lightly to transparent collarbones."

"When subject fails to add up, there's the sum

of my own fingers, vanities, the way

the body shows me just what's mine: the run

of timid freckles sprinting down an arm,

a clavicle to climb, the bones that hold"

In "The Prolific", erasure threatens to disappear the speaker; she is subject to a "He" who inflicts the cruelty of any perfecting impulse. Then, in "What I Hold", we find a reversal, a fully realized transformation: it is the visibility that any body of a poem insists on. The freckles, however timid, are sprinting, and those bones that hold feel decidedly more present than the transparent collarbones beneath the light press of his hand in the earlier poem. The last poem in "What I Hold" reminds me of Robert Frost's infamous poem, or at least how I imagine someone might feel, reading it for the first time, to perceive the seemingly impenetrable stone of a well-made poem break clean open, and find inside it all the facets and light of geode.

Poet Annie Finch calls Piazza an heir to Hopkins, citing the undeniable music in her work. While the sounds and rhythms all throughout this book are that gorgeous, it seems to me the voice of these poems is more skeptic than ecstatic, and that the poems' conceits, self-deprecating wit, agonies and insights, are descended from Donne. Other times, Piazza reads like the best hip-hop; verbal acrobatics that tempers its own swagger with soul. Whomever she cites as influences, whatever resources she draws from, no doubt the voice here is entirely her own, as vulnerable as it is precise, and resounding with terror and love.