REVIEW

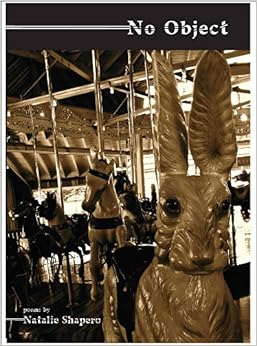

A Review of Natalie Shapero's No Object

Saturnalia Press, 2013 (80 pages)

ISBN: 978-0983368670

Natalie Shapero used to be a lawyer. No surprise there, as the precise language of the legal world informs the poems in her first collection, No Object. Each poem is a delicately structured argument, wrapping point and counterpoint around the reader. Within these poetic syllogisms, a clever kind of logic twists words and phrases, revealing the underbelly of familiar speech. It's almost scientific, and, indeed, the scientific left brain appears to be at work here. No Object is a book obsessed with measurement, exploring that system that governs the self and relationships. "I came within an inch of every inch," states one speaker. In short, within Shapero's highly ordered world, an injunction to the United States to switch to the metric system is not out of place.

This ordered exterior hides an analytical observer, who turns her unshirking gaze on the world. Although she is certainly a part of this world, she also stylizes herself as apart from it. She maintains a distance that allows her to observe the foibles and follies of others. So doing, she seems to lose some of her own vitality. "I am," the speaker states in the opening poem, "highly/lifelike. I highly like life, though in a faraway/and pent-up manner."

In addition to analyzing the world around her, however, the speaker also turns unflinchingly, even vindictively, on herself: "I stared at myself for hours," she admits. Her passive-aggressive tendencies and sexual embarrassments are laid bare before the reader. In "Lean Time," she details the self-destructive habit of reliving an old relationship, comparing it with a woman who eats from the garbage. "Oh I am a wholly worthless person," she explicitly states, in "Though in Zero Gravity." This attitude toward the self, which can come across as self-pitying, is also meticulously self-aware. It is a self-hatred that is, perhaps, simply another kind of self-love. The self-deprecation is further revealed through relationships with others, the ways that each person brings life and death to one another. Relationships seem to be motivated by the impulse toward measurement mentioned before, designed to fill perceived needs. Desires and wants, taken in to the self, blend into one another. As "Examples of How to Search" states,

Hotel on the coast, surrounded now by bodies

of alligators. The cause of death is money

people threw in the fountain, making wishes.

The alligators ate it. I am like that,

taking into my person so many wants.

Shapero also does not shy from the sexual undertones that accompany this preoccupation with measurement. "That's not my hat size, girl," a stranger tells the speaker in "You're Allowed." Indeed, the other characters who populate this book are mostly men, and mostly boors. Just as the speaker is driven by her passivity and self-loathing, the men are aggressive and leering. Male characters forcibly buy the speaker drinks, are compared to the solipsistic Humbert of Lolita, and leer after Vestal Virgins.

The speaker's relationship with these men, ultimately, reflects back on her opinion of herself. A male bird is taught to whistle "in a sexy way," but does so at the speaker only when the cage is draped. As she states, "I really could have been anyone." Yet, in contrast with her own passivity, the speaker does not portray herself as a victim. Interestingly, as the men sexualize the speaker, she also sexualizes them. They are relegated to sexual creatures, and their relationship to women is almost exclusively a sexual one.

Even when the relationship with a male figure is a romantic one, the terms employed are not those of tenderness. "My old love," one speaker ironically states, in a poem about her own self-destructive behaviors. Even the depictions of relationships shy from showing any affection. Is there an irony to the term "lover" when she talks clinically about the men with whom she was "together"? The love in these relationships might be there, on the pages of the old letters that she pores over, perhaps. However, she purposefully avoids showing it—is this her legal training again, or the avoidance of an analytic uncomfortable with emotion?

Yet, even as Shapero avoids emotion, she is also honest about herself in a way that cuts to the core of what it means to be a self-aware human. To be human is to know one's ugliness. As the title indicates, this honesty is often focused in on the self's physicality: "I have my ugly mouth," she writes in the opening poem. And, in "Orange on the Nail," "See the shop/where the model girls are ugly. This only happens at one store,/and every time I'm there they offer me work."

Like Woody Allen, whose presence haunts the pages of No Object, Shapero undercuts this self-hatred with humor.

I never said, like, baby I don't need you

to make me hate myself—I get enough

of that at home.

I live alone.

This tendency is very en vogue (although, perhaps, irony is never really out of fashion). Shapero's speakers are self-aware members of a self-aware generation. The unflinching look at her own destructive tendencies echoes Lena Dunham's fictionalized self in her film Tiny Furniture. The voice that writes many of these poems has the same aphoristic humor of Dunham's Twitter page. And, just as Dunham directs herself in degrading sex scenes on Girls, so Shapero, in a memorable image, recounts a lover who drags her across the floor, leaving rug burns on her backside.

Ultimately, however, No Object transcends the triviality of a Twitter feed. This book complicates self-awareness, acknowledging both its ubiquity and its limitations. As one speaker asks, "how/many times have we all seen fucking Manhattan?" There is more at work here than irony and legal incisiveness, more than polemic. The humiliations and tremors of life are rendered starkly and caustically, but also as lovely things. "No Key" strikes this kind of balance:

It shows on my face. I'm all turned down,

Ill-suited to the lock of it,

the whole unluck of me.

With doors, if you can't see the hinges, it's a push.

Heavy ones you do

With both hands. Which is the way

God doesn't give.

But "A person can only take her own praying so much," the book admits. Rather, we must, like the aging actress, "embody ourselves," stepping into the responsibility of existence, closer to ourselves and to others. The final poem of the book, appropriately titled "Close Space," expresses the speaker's exhaustion with this closeness, yet simultaneously critiques her own desire for distance: "This is America. Let me be/sick of close space, shooting for/bodies off and unknown." She recognizes in herself the American need for autonomy, the need for distance created by technology that makes us uncomfortable even in our bodies, mediating self and self, self and others.

Even so, where there is a point, there is always a counterpoint. Two pages earlier, in "The English End," the speaker describes her person as a place that she inhabits, "like some old Gothic castle," yet also invites the "you" to inhabit as well. "I will," she acknowledges, "give you a place to sleep and make you sad." This, then, is what the body means: it is a place for the self and for others to rest and to be sad. Yet know, she tells the reader and herself, that "you are also loved."